Non-Linear Regression Modeling with Bootstrapping: mtcars

Background & Info

This data comes from the R dataset mtcars and is an expansion on the

example given here.

There is not much data in this set, so we can bootstrap the sample to try to get a more robust picture. Bootstrapping is the process of taking random samples of a dataset in order to have multiple sets to model. With enough samples, this should reasonably give us an upper and lower bound that is more reliable that what would be generated from the residuals of the original dataset.

Let’s strap those boots!

library(tidymodels)

print(mtcars)

## mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

## Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160.0 110 3.90 2.620 16.46 0 1 4 4

## Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160.0 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 0 1 4 4

## Datsun 710 22.8 4 108.0 93 3.85 2.320 18.61 1 1 4 1

## Hornet 4 Drive 21.4 6 258.0 110 3.08 3.215 19.44 1 0 3 1

## Hornet Sportabout 18.7 8 360.0 175 3.15 3.440 17.02 0 0 3 2

## Valiant 18.1 6 225.0 105 2.76 3.460 20.22 1 0 3 1

## Duster 360 14.3 8 360.0 245 3.21 3.570 15.84 0 0 3 4

## Merc 240D 24.4 4 146.7 62 3.69 3.190 20.00 1 0 4 2

## Merc 230 22.8 4 140.8 95 3.92 3.150 22.90 1 0 4 2

## Merc 280 19.2 6 167.6 123 3.92 3.440 18.30 1 0 4 4

## Merc 280C 17.8 6 167.6 123 3.92 3.440 18.90 1 0 4 4

## Merc 450SE 16.4 8 275.8 180 3.07 4.070 17.40 0 0 3 3

## Merc 450SL 17.3 8 275.8 180 3.07 3.730 17.60 0 0 3 3

## Merc 450SLC 15.2 8 275.8 180 3.07 3.780 18.00 0 0 3 3

## Cadillac Fleetwood 10.4 8 472.0 205 2.93 5.250 17.98 0 0 3 4

## Lincoln Continental 10.4 8 460.0 215 3.00 5.424 17.82 0 0 3 4

## Chrysler Imperial 14.7 8 440.0 230 3.23 5.345 17.42 0 0 3 4

## Fiat 128 32.4 4 78.7 66 4.08 2.200 19.47 1 1 4 1

## Honda Civic 30.4 4 75.7 52 4.93 1.615 18.52 1 1 4 2

## Toyota Corolla 33.9 4 71.1 65 4.22 1.835 19.90 1 1 4 1

## Toyota Corona 21.5 4 120.1 97 3.70 2.465 20.01 1 0 3 1

## Dodge Challenger 15.5 8 318.0 150 2.76 3.520 16.87 0 0 3 2

## AMC Javelin 15.2 8 304.0 150 3.15 3.435 17.30 0 0 3 2

## Camaro Z28 13.3 8 350.0 245 3.73 3.840 15.41 0 0 3 4

## Pontiac Firebird 19.2 8 400.0 175 3.08 3.845 17.05 0 0 3 2

## Fiat X1-9 27.3 4 79.0 66 4.08 1.935 18.90 1 1 4 1

## Porsche 914-2 26.0 4 120.3 91 4.43 2.140 16.70 0 1 5 2

## Lotus Europa 30.4 4 95.1 113 3.77 1.513 16.90 1 1 5 2

## Ford Pantera L 15.8 8 351.0 264 4.22 3.170 14.50 0 1 5 4

## Ferrari Dino 19.7 6 145.0 175 3.62 2.770 15.50 0 1 5 6

## Maserati Bora 15.0 8 301.0 335 3.54 3.570 14.60 0 1 5 8

## Volvo 142E 21.4 4 121.0 109 4.11 2.780 18.60 1 1 4 2

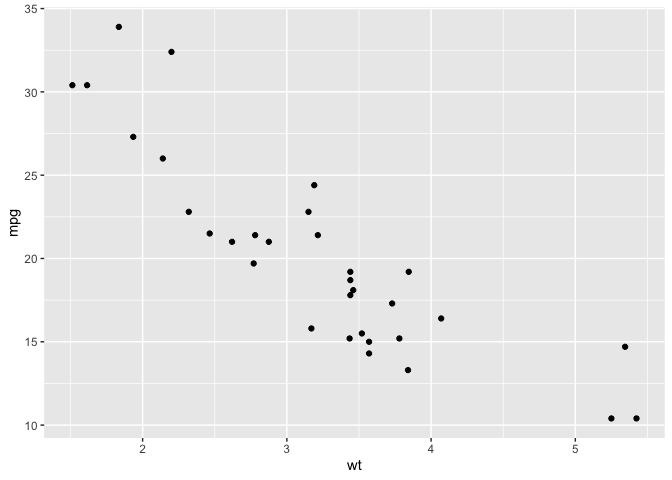

ggplot(mtcars, aes(wt,mpg)) +

geom_point()

We can see that this data may not have a linear relationship. It seems to follow an \(f(x) = \frac{k}{x} + b\) pattern. The base R function for Nonlinear Least Squares can take this relationship between our response and explanatory variable and give us estimates for k and b.

nls_mdl <- nls(mpg ~ k / wt + b, data = mtcars, start = list(k = 1, b = 0))

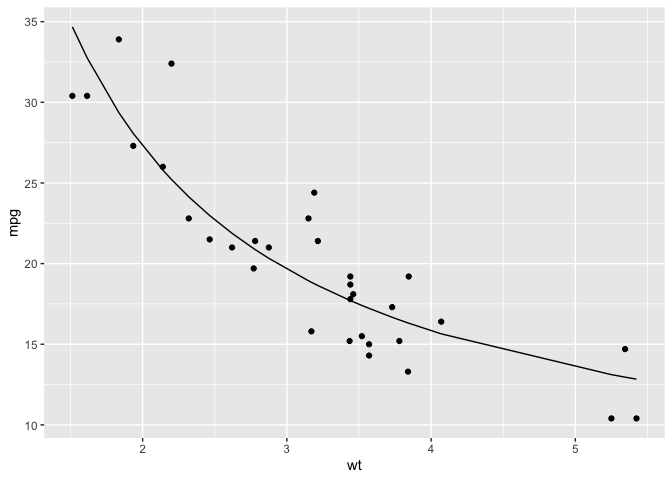

ggplot(mtcars,aes(wt,mpg)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line(aes(y = predict(nls_mdl)))

This does seem like a good fit, but again we may be relying too heavily on a data set that does not have many data points. So, by bootstrapping we can simulate a large number of similar samples which, by the Law of Large Numbers, should give us reasonable upper and lower bounds that more closely reflects the population.

Bootstrapping in tidymodels

boots <- bootstraps(mtcars, times = 2000, apparent = TRUE)

boots

## # Bootstrap sampling with apparent sample

## # A tibble: 2,001 x 2

## splits id

## <list> <chr>

## 1 <split [32/12]> Bootstrap0001

## 2 <split [32/11]> Bootstrap0002

## 3 <split [32/11]> Bootstrap0003

## 4 <split [32/12]> Bootstrap0004

## 5 <split [32/7]> Bootstrap0005

## 6 <split [32/12]> Bootstrap0006

## 7 <split [32/11]> Bootstrap0007

## 8 <split [32/13]> Bootstrap0008

## 9 <split [32/13]> Bootstrap0009

## 10 <split [32/8]> Bootstrap0010

## # … with 1,991 more rows

Notice we have a table with a list-column and an id field for each row.

The splits column contains the bootstrapped sample and it is this data

we would like to model for each and every row. Fortunately, and not

coincidentally, the tidymodels family is here to work with this type

of data.

In order to access the data in splits, we use the analysis()

function as follows:

(boots %>%

slice(1) %>%

pull(splits))[[1]] %>%

analysis()

## mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

## Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160.0 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 0 1 4 4

## Toyota Corolla 33.9 4 71.1 65 4.22 1.835 19.90 1 1 4 1

## Duster 360 14.3 8 360.0 245 3.21 3.570 15.84 0 0 3 4

## Cadillac Fleetwood 10.4 8 472.0 205 2.93 5.250 17.98 0 0 3 4

## Merc 450SL 17.3 8 275.8 180 3.07 3.730 17.60 0 0 3 3

## Fiat X1-9 27.3 4 79.0 66 4.08 1.935 18.90 1 1 4 1

## Pontiac Firebird 19.2 8 400.0 175 3.08 3.845 17.05 0 0 3 2

## Merc 240D 24.4 4 146.7 62 3.69 3.190 20.00 1 0 4 2

## Lotus Europa 30.4 4 95.1 113 3.77 1.513 16.90 1 1 5 2

## Lincoln Continental 10.4 8 460.0 215 3.00 5.424 17.82 0 0 3 4

## Dodge Challenger 15.5 8 318.0 150 2.76 3.520 16.87 0 0 3 2

## Cadillac Fleetwood.1 10.4 8 472.0 205 2.93 5.250 17.98 0 0 3 4

## Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160.0 110 3.90 2.620 16.46 0 1 4 4

## Pontiac Firebird.1 19.2 8 400.0 175 3.08 3.845 17.05 0 0 3 2

## Ferrari Dino 19.7 6 145.0 175 3.62 2.770 15.50 0 1 5 6

## Mazda RX4 Wag.1 21.0 6 160.0 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 0 1 4 4

## Porsche 914-2 26.0 4 120.3 91 4.43 2.140 16.70 0 1 5 2

## Lincoln Continental.1 10.4 8 460.0 215 3.00 5.424 17.82 0 0 3 4

## Toyota Corolla.1 33.9 4 71.1 65 4.22 1.835 19.90 1 1 4 1

## Porsche 914-2.1 26.0 4 120.3 91 4.43 2.140 16.70 0 1 5 2

## Camaro Z28 13.3 8 350.0 245 3.73 3.840 15.41 0 0 3 4

## Ferrari Dino.1 19.7 6 145.0 175 3.62 2.770 15.50 0 1 5 6

## Porsche 914-2.2 26.0 4 120.3 91 4.43 2.140 16.70 0 1 5 2

## Cadillac Fleetwood.2 10.4 8 472.0 205 2.93 5.250 17.98 0 0 3 4

## Ford Pantera L 15.8 8 351.0 264 4.22 3.170 14.50 0 1 5 4

## Dodge Challenger.1 15.5 8 318.0 150 2.76 3.520 16.87 0 0 3 2

## Lotus Europa.1 30.4 4 95.1 113 3.77 1.513 16.90 1 1 5 2

## Honda Civic 30.4 4 75.7 52 4.93 1.615 18.52 1 1 4 2

## Valiant 18.1 6 225.0 105 2.76 3.460 20.22 1 0 3 1

## Merc 240D.1 24.4 4 146.7 62 3.69 3.190 20.00 1 0 4 2

## Datsun 710 22.8 4 108.0 93 3.85 2.320 18.61 1 1 4 1

## Merc 450SE 16.4 8 275.8 180 3.07 4.070 17.40 0 0 3 3

How would this work in the context of tidymodels though? First, we

need to write a function which will properly extract the data from our

bootstrap set, which technically is an rset object.

bootstrapNls <- function(dat){

nls(mpg ~ k / wt + b, analysis(dat), start = list(k = 1, b = 0))

}

boot_summary <- boots %>%

mutate(model = map(splits, bootstrapNls),

summary = map(model,tidy)) %>%

unnest(summary)

Now we have the parameter statistics and p-values for each one of our bootstrapped samples. Let’s see how these parameters are distributed.

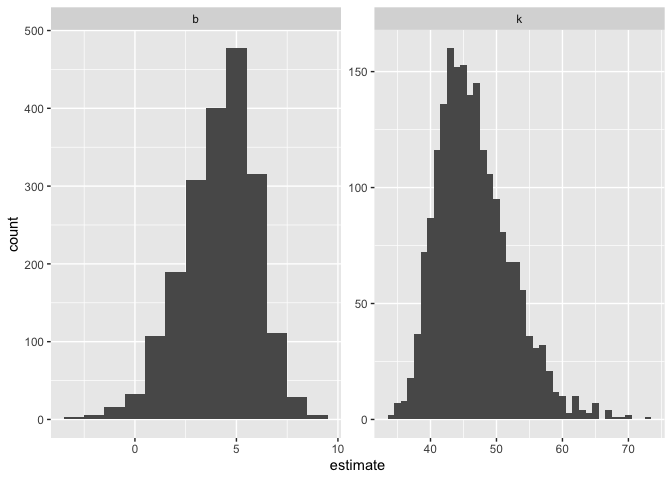

ggplot(boot_summary, aes(estimate)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 1) +

facet_wrap(vars(term),scales = "free")

Interestingly, we get a left-skewed distribution for b and a right-skewed distribution for k.

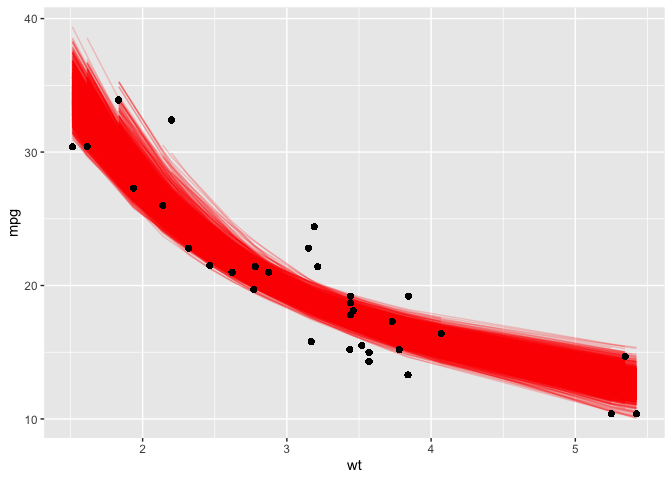

Now, we can try plotting our models to see what the bootstrapped variance is, which gives us an idea as to what the true confidence interval should look like.

boot_aug <- boot_summary %>%

mutate(augmented = map(model,augment)) %>%

unnest(augmented)

ggplot(boot_aug, aes(wt,mpg)) +

geom_line(aes(y = .fitted, group = id), alpha = .2, col = "red") +

geom_point()

And look at that! We are given a great idea as to what the most likely range of regression curves would realistically be had we more data.